Rape is a theoretical Crime: Part 5 - Justice in the justice system

The purpose of the justice system is not to find justice for victims. It is to ensure a fair trial for people accused of crimes and then punish the people who are found guilty.

This is part five of a series on sexual violence.

Part One: The Data examines the available data on rape and sexual assault in Australia, which shows that men have raped or sexually assaulted at least one quarter and possibly more than half the women in Australia.

Part Two: Understanding Rape Myths looks at rape myths and how they are used to obscure the reality of sexual violence.

Part Three: Shame Must Change Sides on Gisèle Pelicot’s declaration that ‘when you’re raped there is shame, and it’s not for us to have shame, it’s for them’ and the effect of shame on people who have been raped or sexually assaulted.

Part Four: Why do men rape? There is no simple or single answer to this question but believing in rape myths and shamed masculinity are common in men who rape. This might give us a path to prevention.

This article is about rape and sexual violence. Helplines are listed at the end. Please call them if you are hurt, shaken, scared, in pain or you just want someone to talk to.

In 2015, a week after being acquitted of sexually assaulting a 17 year old girl, Mitch Peggie raped a 21 year old woman in Brisbane.

During the second trial, the (very) young woman was cross examined by Mitch Peggie’s barrister, Doug Wilson, who asked her if she was just a liar who claimed rape because she didn’t think Peggie treated her well enough after consensual sex. He showed a photo of her underwear to everyone in the courtroom and suggested that she must have wanted sex if she wore such nice lingerie. He asked her if she was ‘moaning’ and ‘gasping’ in pleasure during the rape and looked scornful when she denied it. Peggie and the woman exchanged hundreds of text messages before the date. Some were flirty but many were Peggie making crude and overt sexual demands. Each time the woman responded by attempting to laugh it off or explicitly stating that she would not have sex with him on their date. Her rapist’s lawyer tried to use this to argue that she knew what Peggie expected from the date and must therefore have consented to sex with him.

“I felt so alone and isolated up on that witness stand, like everyone in that room was judging the person I was based on that one night, that one thing that happened to me”, she wrote afterwards.

She was alone in a courtroom designed to be intimidating, surrounded by a judge, court staff, the jury, the lawyers, the accused, his supporters, journalists and anyone else allowed to watch (sexual assault trials are often but not always held in closed courts). The defence lawyer can suggest and insinuate and sneer and say things like ‘I put it to you that you wanted to have sex with him’ about the man who raped her. He can track through every minute of the lead up to the rape, jumping on every tiny, missed detail as if it’s proof she’s a contemptible liar rather than evidence that she has been traumatised, and he can do it for days as all those people watch in silence.

Inexplicably, under such pressure, that young woman held her nerve and gave her evidence – even if she did have to leave the room in tears because of what she described as ‘constant badgering’ by the defence lawyer.

The jury believed her and Peggie was found guilty of rape.

He appealed the conviction but the following year the appeal was dismissed. He would have been eligible for parole in January 2020.

I don’t know if the woman found justice in a conviction after the two years Peggie spent dragging her through humiliation after humiliation in court, trying to deny a rape that even a Queensland jury and appeal court said he committed. I hope she got something from it to help her reclaim herself and everything he tried to take from her.

Another women reportedly told police Peggie tried to use threats and blackmail to force her into unwanted sex (i.e. rape) and yet another woman said he handcuffed and sexually assaulted her. There were also claimsmade to Crime Stoppers that Peggie lied about providing a path to citizenship to extort sex (i.e. rape) from vulnerable migrant women. No charges have been laid against him regarding these claims. He may well not be guilty of these crimes, but the justice system cannot tell us the answer to a question it has never asked.

Bruce Lehrmann, having lost his hat, is now scrabbling his way back to pretend he can roar at a lion. When he’s not allegedly nicking cars in Tasmania, he’s gearing up for another rape trial in Queensland and an appealagainst the finding, on the balance of probabilities, that he raped Brittany Higgins in 2019. I have no sympathy for him at all, but I do wonder whether he thinks that ducking a criminal conviction was justice. Did Brittany Higgins find justice in Justice Lee’s judgement? Or is she, under constant attack for being attacked, still too mired in ruinously expensive battles of the justice system to find justice?

Luke Lazarus was accused of raping Saxon Mullins behind a bar in Kings Cross in 2016. He might also say he beat the system because he doesn’t have a conviction of rape recorded against him, but he doesn’t have an acquittal either. Over five years, Lazarus was convicted, overturned on appeal, retried, convicted again and the second conviction quashed on appeal. The NSW DPP decided to not attempt a third trial. Can we call him a rapist? Not really. But equally, he cannot claim the system says he’s not a rapist. I don’t know if he would call this justice. Saxon Mullins called it ‘total and utter traumatisation’.

The justice system gave Lehrmann, Peggie and Lazarus the right to spend years humiliating the women they raped. It says they were entitled – required – to do it in front of an audience of strangers because this is how the justice system ensures justice is done.

A woman who asked to be known as Lila contacted me recently because she wanted me to include a positive experience of the justice system. She said, ‘I went to a party at the end of lockdown. There was a lot of alcohol and other stuff floating around. The end of lockdown was a weird time and I think lots of us were doing stuff we wouldn’t usually do. Without going into too much detail, I met a man at the party and at the end of the night he raped me in a spare room.’

‘One of my friends is a cop and I called him the next morning. He took me to the hospital and the police station and helped me understand the whole process. The man who raped me admitted it. From the beginning he admitted it. They charged him and he pled guilty and apologised in court. And he really apologised, not a sorry-not-sorry apology. He apologised like he had really thought about it and he meant it. He got a very light sentence, but I was ok with that. I actually would have preferred it if he got mandatory counselling or therapy instead of a few months in prison, but it’s not like the sentence upset me.’

‘To be clear, I was unbelievably lucky. I had a cop with me, on my side, guiding me through and making sure I got treated well. My rapist admitted it from the get-go so there was no trial, just a plea hearing and a sentencing hearing. It was all processed pretty quickly and everyone was really sympathetic and supportive. I know that doesn’t happen for most people, but I just wanted to let you and your readers know that it is possible.’

‘Unbelievably lucky’ … because the man who raped her didn’t choose to drag her through years of additional torment in the justice system. Is that justice? Lila wasn’t sure when I asked her, but she should not have to feel guilty for finding something akin to justice in the justice system.

What is Justice?

The Oxford dictionary defines justice as ‘conformity (of an action or thing) to moral right, or to reason, truth, or fact; rightfulness; fairness; correctness; validity’.

In other words, justice is in the eye of the beholder. Fairness, rightfulness and validity are subjective ideas, based on perceptions of who was right and who was wrong. Very few people ever really believe they have done the wrong thing. Men who commit rape and sexual assault almost always find a way to believe that either what they did wasn’t wrong (she’s a liar) or that the person they did it to could not be wronged (she was asking for it).

Some people who have been subjected to sexual violence want vengeance. They want him to be convicted, shamed and punished because that’s the only way he might feel something of the shame and punishment he inflicted on them. There’s evidence that police, the gatekeepers of the justice system, frequently believe women who report rape are ‘vengeful liars’ seeking retribution for rejection after consensual sex. Or, they might use the absence of vengeful thoughts as another excuse to disbelieve women - if you were telling the truth you’d want revenge so if you’re concerned about him you must be lying.

Vengeance and punishment, however, are rare motives for people who seek justice for sexual violence. They are far more likely to want safety (for themselves, the people they care about and other women he might hurt). The violence itself, however, is proof that they have no power over his choices and it can take months, even years, to overcome that feeling of powerlessness and report his crimes.

Most of all they want recognition. Far more than prison sentences or convictions, people who have been raped or sexually assaulted say they want recognition of what was done to them and taken from them. They wantrecognition of the work they must do to recover, and for everything they cannot do or will lose in all the grotesquely unfair demands of that recovery. They need to know that others see the pain they feel and understand the assault was not their choice or their fault. Ideally, they would get this from the man who hurt them as well as from the people and institutions in their community. Lila, the ‘unbelievably lucky’ rape victim got that. Most people do not.

The most compelling explanation of justice I’ve found is what the researchers described as kaleidoscopic justice, which sees justice as a ‘constantly shifting pattern, continually refracted through new experiences and perspectives, with multiple beginnings and no finite ending’. This description encapsulates what I’ve seen in so many people who have told me about the sexual violence they’ve survived – their needs and perspectives of justice are always in motion, even years after the event. But for almost all of them, the underlying need for recognition, participation, dignity and prevention are always close to the surface and the re-traumatisation from the legal system is almost always because it ignores those needs.

Just adjudication

The British common law system, on which Australia, India, Canada, New Zealand and the USA all base their legal system was developed over more than a thousand years. It was primarily a means of arbitrating disputes over property and taxes as the monarchy slowly absorbed powers previously held by the church and feudal lords. Rape, as I wrote in part two of this series, was until very recently, a property crime against the man who had an ownership claim over a woman’s body. Justice for rape was given in the form of recompense for the devaluation of his property.

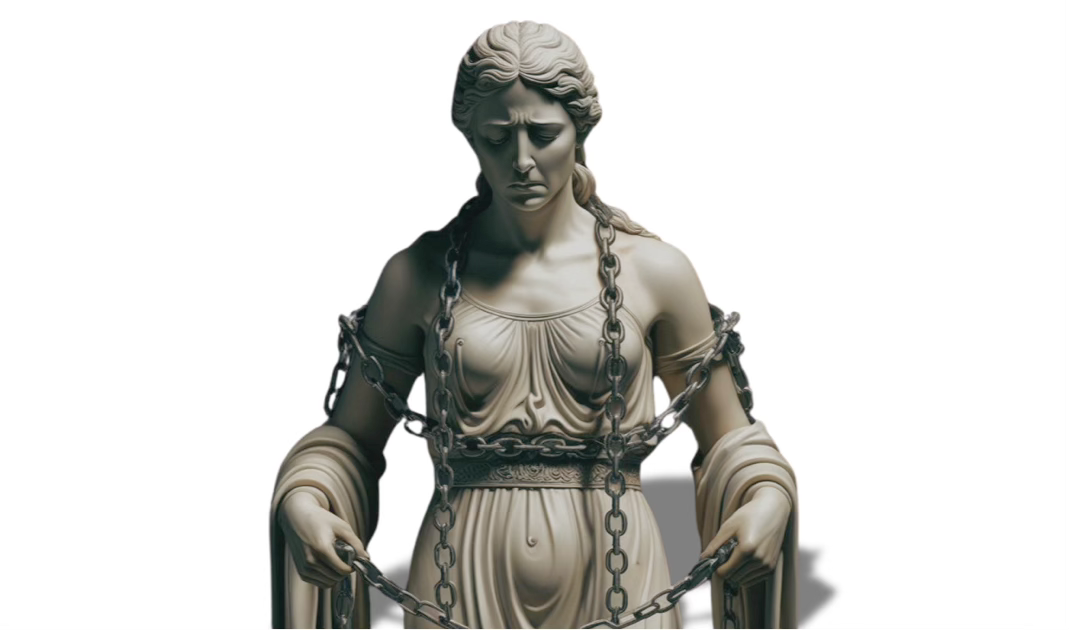

The legal system is often referred to as the justice system, but justice is not its purpose. The criminal system exists to enforce the law, adjudicate claims of wrongdoing, and punish wrong doers. It acts on behalf of the state, not the victim, and its claim to being a system of justice is not in the outcomes it produces (punishment for wrong doers) but in the method by which it determines who is or is not deserving of punishment.

No person in a democracy, no matter how rich or powerful they are, can have their own police force - an organisation of thousands of trained enforcers who have a legal right to arrest and question people, or force them to hand over documents, DNA, fingerprints and digital communications. Very few people have millions of dollars to spend on lawyers and experts who can present a compelling case in court. No one has the right to collect taxes and use that money to incarcerate someone for years, even decades. Only the state (governments, courts, parliaments, police, prisons, all working together and supposedly keeping each other in check) has this power.

All of which means that there is inherent unfairness in a legal system that pits the state against an individual.

The legal system attempts to redress that unfairness and ensure every accused gets a fair trial by imposing strict rules and limits on the state:

The burden of proof is on the state, meaning that everyone accused of a crime is presumed to be innocent and does not have to prove it, rather the state must prove they are guilty.

The standard of proof the state must achieve is very high, proving guilt beyond reasonable doubt means that even if a jury thinks it’s quite likely he is guilty, they still have to acquit.

A jury must assess all the evidence provided by the state. They must be people from the accused’s community who have no prior knowledge of the alleged crime, and they must make their decision based solely on their impartial assessment of evidence presented in court where the judge can see it and the defence can question it.

Stemming from these basic principles, there are rules for criminal proceedings and while there are exceptions, they mostly apply to all trials for sexual violence

The accused cannot be compelled to give evidence against themselves,

People the accused trusts, such as priests and spouses and doctors, cannot give evidence against them.

They have the right to have a lawyer test the evidence the state has collected against them and this is so important that the state will pay for it if the accused can’t.

The jury can only hear information about the crime with which he is charged. His history, public opinion about his guilt, or expert analysis not presented and tested in court is such a risk of influencing the jury that even knowing about it can cause a mistrial (as it did in Bruce Lehrmann’s trial for raping Brittany Higgins).

(It's worth noting that these rights are only relevant to the criminal system where they address the massive power imbalance between the state and a single person. If a woman you know says your mate sexually assaulted her and you have to make a decision about whether to invite him to your next BBQ, you can’t hide behind innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. You’re not the state and not getting an invite to a BBQ is not the same as being incarcerated.)

The rights given to the accused are the justice in the justice system. Without them, government ministers could simply declare that someone who irritated them is a criminal, lock that person in a cell, refuse to allow them to speak to anyone, and keep them there until they die. Even without going to such extremes, if we start watering down the protections people have against the power of the state, the people who will suffer are the ones already over-policed and disproportionately incarcerated – First Nations people, anyone with a mental illnessor addiction, people living in poverty, and children from trauma backgrounds.

So, there is an unresolvable conflict between protecting people from abuses of power by the state and protecting people from abuses of power by other people. There is no law reform that can resolve that conflict or enable the justice system to give people who have been raped the recognition, dignity, and participation they need to find justice. The criminal law system cannot find justice in the intimate terrorism of most sexual violence. There might be an argument for the rare cases of stranger rape to stay in the legal system and there is definitely an argument for giving people who have suffered sexual violence the option to go through the legal system if they choose, but decades of reform have not made any difference to persistent rape myths and the trauma the legal system inflicts on rape victims. It’s well past time we stop looking for alternatives and start making ‘alternative justice’ the primary justice pathway for sexual violence.

The next instalments in this series will look at the results achieved by restorative justice programs in Australia and around the world and the other options available to people who have been raped and sexually assaulted in Australia.

Discount offer for readers

20% DISCOUNT plus free postage on any book purchase from my store.

Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children

Fixed It: Violence and the Representation of Women in the Media

Teaching Consent: Real Voices from the Consent Classroom

Discount code: 20Fairy

Podcast

The Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children podcast, loosely based on the themes in my book of the same name, is out now. You don’t need to read the book to listen to the podcast, but you can find out more about both here.

Helplines

In an emergency, where you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call police on 000

If you want to ask for anonymous advice for yourself or someone you know, call one of the helplines listed below or talk to a trusted GP or nurse practitioner at your local medical centre.

1800RESPECT

24/7 support for people impacted by sexual assault, domestic and family violence and abuse.

Ph: 1800 737 732

www.1800respect.org.au

Sexual Assault Crisis Line

24/7 Support for victims of sexual assault

Ph: 1800 806 292

www.sacl.com.au

Full Stop Australia

24/7 National violence and abuse trauma counselling and recovery service

Ph: 1800 385 578

www.fullstop.org.au

Men’s Referral Service

24/7 Support for men who use violence and abuse.

Ph: 1300 766 491

www.ntv.org.au/get-help/

Blue Knot Foundation

Phone counselling for adult survivors of childhood trauma, their friends, family and the health care professionals who support them. Available between 9am and 5pm, every day.

Ph: 1300 657 380

www.blueknot.org.au

Lifeline

24/7 crisis support and suicide prevention services.

Ph: 13 11 14

www.lifeline.org.au

Suicide Call Back Service

24/7 suicide prevention support

Ph: 1300 659 467

www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au