Rape is a theoretical crime: Part 1 - The Data

In 2020, then Victims’ Commissioner, Dame Vera Baird QC, said the UK’s 1.6% conviction rate was ‘the effective decriminalisation of rape’. The conviction rate in Australia is less than 2%. Why?

This was originally going to be a single article, but it got so long and unwieldy that I had to break it up into manageable pieces. This first piece is about the national data and how it underestimates the prevalence of sexual violence in Australia. I’ll publish the rest of the series over the next couple of weeks. Parts two and three will cover rape myths and how they affect police, courts, law reform, and most of all the people who’ve been raped and the people who commit rape. The final part to the series will look at alternatives to the legal system that have been tried in Australia and other parts of the world.

Data Summary

Reading long articles about data on rape and sexual assault is not everyone’s idea of a good time. So, for all the people who can’t or simply don’t want to read all the analysis, here’s the summary:

More than 400,000 people were sexually assaulted in Australia in 2023. The MCG at full capacity would not be enough for one quarter of them.

A total of 4,564 people (96% male) were convicted of sexual assault in 2023, which is roughly the same as the number of people working in Parliament House in a sitting week.

National data does not include information about trans or non-binary people in crime or court data, but people who live outside the gender binary are often both vulnerable and targeted. The data also does not include information about race, but people from migrant and refugee communities face additional barriers to seeking support and have increased vulnerabilities to predatory men, which suggests they probably experience disproportionate levels of abuse. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women experience very high rates of sexual violence due to the intergenerational trauma of colonisation. This is not included in the national data.

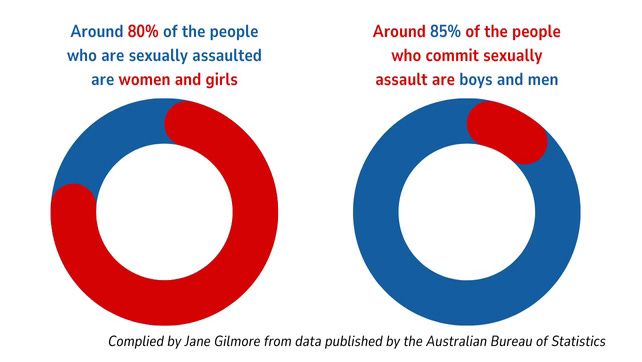

The data that is available says this is a highly gendered crime.

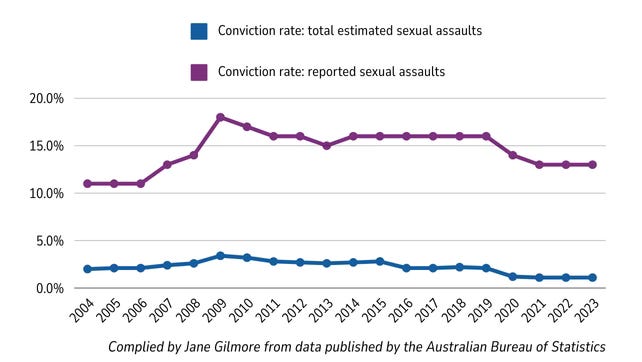

Data also shows that Australia’s conviction rate for rape and sexual assault is decreasing and by 2023, it was roughly 1.1%. In other words, rape is a theoretical crime, or, to quote Vera Baird, it is effectively decriminalised.

Infographics and statistics are useful ways to demonstrate the scale of sexual violence, but all these data are about people. Too many people. I know some of them. So do you. In fact, we know many more of those people than we think we do.

Are the ‘facts’ we’re given about sexual violence accurate?

Anything you see or hear quoting ‘facts’ about gender based violence that includes the phrase ‘since the age of 15’ almost certainly comes from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ Personal Safety Survey (PSS). The PSS is the national source for almost all data on gender based violence and it’s where we get the commonly cited statistic that ‘1 in 5 women has experienced sexual violence since the age of 15’.

The data from the PSS is robust but that doesn’t mean it is accurate. The PSS excludes anyone who doesn’t live in a ‘private dwelling’ and can only report what people are able to tell a stranger about their most traumatic experiences. The PSS is not fact, it’s an estimate of the number of people in secure housing who are able to talk to a PSS interviewer about the violence someone has committed against them.

An even more robust (larger dataset and of longer duration) study of Australian women estimated that at least half the women aged 24 to 30 in 2019 had experienced sexual violence in their lifetime. These results are not directly comparable to the PSS findings because they’re measuring lifetime experience rather than since the age of 15 experience, but it demonstrates that different surveys obtain different results and we should therefore be wary of counting the results of one survey as fact, especially given its exclusions and limitations (more details below).

The most accurate statement we can make about sexual assault and rape in Australia is: At minimum, one in five women in Australia have experienced sexual violence in their lifetime, although the true rate is likely to be significantly higher.

Reported vs unreported sexual violence

Crime data is not useful in understanding prevalence of sexual violence because evidence says that most people who are sexually assaulted or raped do not report to police.

Of the people who were able to tell 2021/22 PSS interviewers about being sexually assaulted, only 8 percent said they reported the assault to police. This result may have been skewed by the COVID lockdowns at the time, but PSS data since 2005 indicates reporting rates have been decreasing over the last twenty years. Given the downward trend over four iterations of the PSS and that this is reflected in estimates from similar jurisdictions (Canada, New Zealand, UK and the US) it’s likely these numbers are reasonably accurate.

Estimated rate of reporting sexual assault to police in Australia according to PSS data:

2005 - 19%

2012 - 17%

2016 - 13%

2021/22 - 8%

Source: Australia Bureau of Statistics, Personal Safety Survey

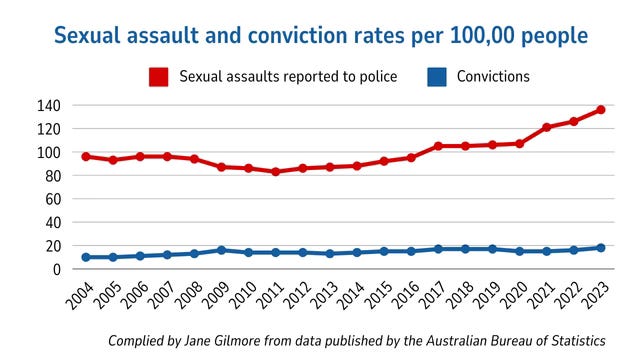

Despite this, victimisation rates (the number of reports to police per 100,000 people) are trending upwards. Which means more people are being sexually assaulted each year and fewer of them are telling police when it happens.

Meanwhile, the number of cases that go from police to the courts and reach a conviction is virtually unchanged in the last twenty years.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Recorded Crime - Victims, Criminal Courts - Australia

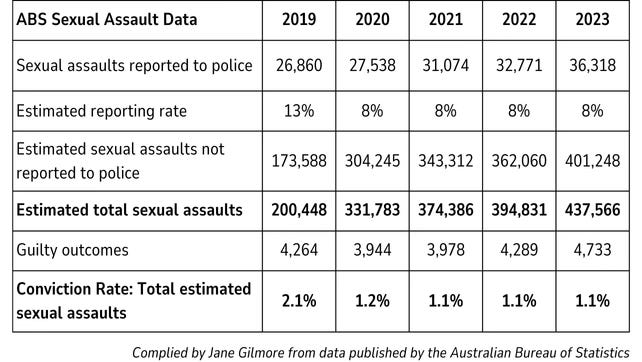

The Australian Bureau of Statistics crime data on sexual assaults is robust from 2010, but before then there were difficulties matching data across states. There are some issues with data matching in my calculations (explained more in the details below) but the graph above shows a rough picture of the last twenty years. The table below is the last five years (the table with the full 20 years of data won’t fit into this format, so this is an indication of what it looks like).

Notes: This data is a rough estimate. The police reports and court outcome data comes from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and should be very reliable after 2010. Data matching is not exact because crime data is reported on calendar years and court data on financial years. Additionally, sexual assault trials can take a long time and it’s unlikely they would be finalised in same year the assault was reported to police. The calculations hinge on the reporting rate, which is the estimate quoted above from the PSS. As outlined above and below, the PSS excludes people who don’t have secure housing and people who can’t or don’t want to discuss their traumatic memories with a stranger. It seems logical if they were included it would increase the number of people who haven’t reported to police but there’s no way to know for sure. The reporting rate estimate in the 2021/22 PSS was a sharp drop from the previous iteration of the survey, which may be due to COVID lockdowns. It's worth noting that even if it had remained unchanged from the 2016 rate, the conviction rate would still be below 2 percent.

That’s a quick outline of the data, what it tells us and what it can’t tell us. If you want more details, the second half of this article includes more information on the strengths and limitations of the PSS data and what it can tell us about unreported and undisclosed rape and sexual assault.

If you’ve got enough for now but you want to read the next parts of the series, you can subscribe here so you don’t miss any of them.

How many people are raped in Australia each year?

Despite the all the data, the real truth is that we don’t know, but it’s definitely more than the commonly used statistics indicate.

The PSS is a statistically robust survey of between about 12,000 (2021/22) and 21,000 (2016) people in Australia and it asks very detailed questions about their lifetime experiences of violence.

The PSS started with the Women’s Safety Survey in 1996, then in 2005 it was expanded to include men and renamed as the Personal Safety Survey. The survey was repeated in 2012, 2016, and 2021-22. The huge number of participants and the reiterations over time mean the data it collects are robust and reliable. The ABS has rigorous methodology, well-trained interviewers, and experienced statisticians who work hard to produce trustworthy data.

The problem with the way we use and talk about this data is not because the data is unreliable – it isn’t. It’s because the many organisations that cite this data do so without explaining what it is and what it isn’t.

Every PSS since 2005 has excluded people who do not live in a ‘private dwelling’. This means the survey questions are not even asked of anyone who is homeless or is in hospital, or is staying with friends or family, living in a domestic violence refuge, hotel, motel, hostel, short-stay caravan park or nursing home. At least 45% of all women and girls needing homelessness assistance identify family and domestic violence as a cause and they are not included in this data. As another example of excluded data, the 2020 Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety heard submissions that up to 50 sexual assaults occur in aged care each week. People living in aged care are excluded from the PSS, so these sexual assaults not included in the data.

In other words, all the people most likely to be suffering the effects trauma are excluded from the survey about traumatic violence.

Of the people who are included, the response rate in 2021-22 was 52% and the PSS interviewer cannot (and should not) ask people who refuse to complete the survey why they’re saying no. Maybe some of the 48% who didn’t want to answer questions about physical and sexual violence were just bored by the topic. Maybe they were too busy, or they were in the middle of a good book and didn’t want to be interrupted. It seems likely though, that at least some of them were not willing or simply not able to tell a stranger about their most traumatic moments. On top of that, the 2021-22 PSS was conducted during the COVID years, when it was likely that partners and children were at home. The interviewers were told to make sure the survey was conducted in a ‘private place’, but I’ve spoken to far too many women who live with men who terrify them to believe that an abused woman would feel safe answering questions about her abuser when he’s somewhere in the house. The PSS data also indicates the person most likely to commit sexual violence is a woman’s male partner, so, again, it seems logical that at least some of the people who refused the survey have had experiences they can’t or don’t want to talk about, but there is no way to know for sure.

The other point to note about the PSS data on sexual violence is the question itself.

‘Has any man/woman including your current partner ever forced you, or tried to force you, into sexual activity against your will?’

There is no information in the questionnaire or the prompt cards about how people understand the word ‘force’. Would a woman answer yes to this question if her husband told her she would not be allowed any money for food if she said no to sex? What about a woman whose boyfriend was relentlessly asking ‘now, how about now, can I do it now, now? NOW?’ and kept going until she ‘gave in’? What about a woman whose partner is silently terrifying but only occasionally physically violent and while she’s not explicitly threatened, she’s too scared to say no? Some of those women might understand intimidation and coercion as force, but some would not, and if they were asked the question and their answer was ‘no’, they would be recorded in the PSS as never having experienced sexual violence.

The PSS itself hold clues about how much women’s perception of sexual violence impacts their ability to answer this question. In the 2021-22 survey, 73% of women who were able to say yes to the question about whether they had experienced sexual violence in the last ten years also said they did not perceive the ‘incident’ as a crime at the time, and 64% of those women said this perception has changed over time, mostly due to self-education. Which means around half the women who have recently been sexually assaulted would probably have said no to the question about experiencing forced sexual activity if they were asked about it in the immediate aftermath.

I don’t think there is a reliable statistical method to control for excluding people who are likely to have experienced sexual violence and also factor in the potential for being unable to answer the question (if you are a statistician and you know how this could be done, please let me know) so all I can conclude from this is that the prevalence data from the PSS must be significantly underestimated.

Again, this is not because the ABS isn’t doing a robust survey – they are – it’s just the inherent difficulty of surveying people about trauma. It would be grossly unethical to force everyone to answer or to ask for intimate details of people’s sexual experience and relationships without their consent. It is important that we know how many people are subjected to violence, how often, who did it, where and how they did it. We need that information to make sure the services are available and properly funded. We also need it to make sure prevention and intervention strategies are targeted and effective, but as important as those things are, none of them could justify forcing unwilling people to answer questions about sexual violence.

What we can do, however, is understand the data and be more informed and accurate about how we use it.

No: one in five women have experienced sexual violence since the age of fifteen

Better: at least one in five women have experienced sexual violence since the age of fifteen

Even better: at least one in five women have experienced sexual violence since the age of fifteen, but this number is likely to significantly underestimate the actual prevalence.

How many people commit rape in Australia each year?

No one can answer this question. We can make a guess at the total number of rapes and sexual assaults that happen, as I have above, but we don’t know how many people are responsible for them. Crime data is clearly not helpful and all the robust survey data we have about victimisation doesn’t ask about perpetration.

The unknown factor is how many women each violent man sexual assaults. If 400,000 women are sexually assaulted in a year, it might be 100,000 men who choose to commit those crimes, or it might be 300,000. As far as I know, there is no reliable data in Australia that can get us any closer to an estimate than that.

A study published in 2024 found that one in six men and one in 20 women admitted to perpetrating one or more forms of sexual assault during adulthood. Men were more than twice as likely to have perpetrated more than one form of sexual violence, they were two to five times more likely to commit sexual assault and image based abuse and twice as likely to commit sexual coercion and harassment. The data doesn’t tell us enough to answer the 100,000 or 300,000 question, but it is an indication that we probably all know at least one man who has perpetrated sexual violence.

While it doesn’t answer the question of how many rapists are there in Australia, this very detailed report from QUT outlines the complications of collecting this data and the very limited information that was available in 2022.

Why is the conviction rate so low?

There are three reasons: low reporting rates (as outlined above), low proceeding rates (around 35% of sexual assaults reported to police in 2022 went to court), and low conviction rates (35% of sexual assault defendants were found guilty in 2022/23). To put that in context, 69% of non-sexual assault defendants were found guilty in 2022/23.

I’ll get into the police and court attrition in parts two and three of this series, but the huge number of people who do not report being sexually assaulted or raped is the largest part of this story and it’s worth digging a bit deeper into the data on why people are so reluctant to report to police. ABS data doesn’t deal with police responses or reasons people might not trust police and I’ll come to those in part two and three, but it does tell us something about the low reporting rate.

Unreported Sexual Assaults

In 2021/22, women in secure housing who were able to tell PSS interviewers about being sexually assaulted by a man were given a list of 15 possible reasons for not reporting to police (they could choose more than one) and the top five reasons were:

Felt they could deal with it themselves (34%)

Did not regard the incident as a serious offence (34%)

Felt ashamed or embarrassed (26%)

Did not think there was anything the police could do (22%)

Did not know or think the incident was a crime (22%)

The PSS defines sexual assault as: ‘An act of a sexual nature carried out against a person's will through the use of physical force, intimidation or coercion, including any attempts to do this. This includes rape, attempted rape, aggravated sexual assault (assault with a weapon), indecent assault, penetration by objects, forced sexual activity that did not end in penetration and attempts to force a person into sexual activity.’

The PSS sexual assault data excludes unwanted sexual touching - this is defined as sexual harassment and forms part of another dataset in the PSS.

What is going on for all the women who think such crimes are something they should deal with themselves? Or that they are not a serious offence? The data gives us an indication of what is happening, but it doesn’t tell us why it’s happening. There may be some clues in the PSS data, which shows that the person mostly likely to sexually assault a woman is her intimate partner. Women who are sexually assaulted by their partner have difficulty recognising it as rape and are less likely to report sexual assault than if it was done by a stranger. PSS data indicates that women in secure housing who can disclose sexual assault report that strangers are the perpetrators in around 20 percent of sexual assaults.

So it’s likely that most of the women who don’t report are being sexually assaulted or raped by men they know and probably by men they want to love. They struggle to recognise it as rape and might be ashamed, afraid or conflicted about reporting him to police.

Who do they tell?

The 2021/22 and the 2016 PSS estimated that around half the women who had been sexually assaulted by a man didn’t tell anyone at all. Of the half who did tell someone, the most common confidant was a friend or family member.

If the 8% reporting rate is correct, over 200,000 of the women were sexually assaulted in 2023 didn’t or couldn’t tell anyone about it.

If you are one of those women, I hope it helps to know that you are not alone. You almost certainly know other women who have been through what you’ve been through. They might understand and empathise more than you think they will. If you can find someone you trust, it might help to tell them. No one should have to carry the weight of that at all and they certainly should not need to do it alone. If you don’t want to tell someone you know, there is a list of sexual assault services at the bottom of this article. They’re chronically underfunded so they might take a while to answer your call, but they will answer, and they can help.

If you’re still reading at the end of almost 3,000 words about sexual assault data, thank you and I hope it was useful. If you want to read the next pieces in this series and haven’t already subscribed, you can sign up below. I will do my best to keep them all outside the paywall, but if you can afford to subscribe it’s only $10 a month and every subscriber helps me slice away time from chasing paid work to do this work.

Note: some of the data and analysis in this piece was taken from my upcoming book about violence prevention education, which will be published by Allen & Unwin next year.

Also, in case you haven’t seen it, my new podcast is out now: Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children is loosely based on the themes in my book of the same name. You don’t need to read the book to listen to the podcast, but you can find out more about both here.

Helplines

In an emergency, where you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call police on 000

If you want to ask for anonymous advice for yourself or someone you know call one of the helplines listed below or talk to a trusted GP or nurse practitioner at your local medical centre.

1800RESPECT

24/7 support for people impacted by sexual assault, domestic and family violence and abuse.

Ph: 1800 737 732

Sexual Assault Crisis Line

24/7 Support for victims of sexual assault

Ph: 1800 806 292

Full Stop Australia

National violence and abuse trauma counselling and recovery service

Ph: 1800 385 578

Rainbow Sexual, Domestic and Family Violence Helpline

Support for anyone in Australia who is from LGBTQ+ communities (or their family and friends) who has recently or in the past experienced sexual, domestic or family violence

Ph: 1800 497 212

Say It Out Loud

Support and information for LGBTIQ+ people in a domestic and family violence relationship

Men’s Referral Service

24/7 Support for men who use violence and abuse.

Ph: 1300 766 491

Blue Knot Foundation

Phone counselling for adult survivors of childhood trauma, their friends, family and the health care professionals who support them.

Available between 9am and 5pm, every day.

Ph: 1300 657 380

Lifeline

24/7 crisis support and suicide prevention services.

Ph: 13 11 14

Suicide Call Back Service

24/7 suicide prevention support

Ph: 1300 659 467