Rape is a Theoretical Crime: Part 3 - Shame Must Change Sides

Gisèle Pelicot, a 72 year old French woman, has become a worldwide icon for her refusal to accept shame after being raped by more than eighty men. Why does rape shame have such power?

This article is about rape and sexual violence. Helplines are listed at the end. Please call them if you are hurt, shaken, scared, in pain or you just want someone to talk to.

In 2020 police discovered that Gisèle Pelicot’s husband of fifty years had, for at least ten years, been systematically drugging her, raping her and inviting other men to her home to rape her.

He was caught because a vigilant security guard saw him filming up a woman’s skirt in a supermarket and reported him to police. The woman he filmed decided to press charges and when police seized Dominique Pelicot’s computer they found videos of more than 80 men raping Gisèle.

If the security guard who caught him and the woman who pressed charges not taken the upskirting so seriously, men would still be raping Gisèle Pelicot today.

These men are not monsters, despite their monstrous acts. They’re just ordinary men. A soldier, a journalist, a truck driver, a baker, a builder. Many of these men have wives, children, grandchildren, friends, and colleagues who may well have thought they were ‘good men’. In fact, they are rapists.

Dominique Pelicot admitted to raping Gisèle. He said he drugged her and raped her two or three times a week, which was more than the images from his computer indicated. He testified in court that he had drugged her and invited other men to come to her home to rape her. He said they knew she was drugged and unconscious. The videos showed the men moving her inert body as they raped her. In some videos, she was even snoring.

Despite all this evidence, some of the men who raped Gisèle have tried to excuse themselves or even blame her. “It was a game,” one of them said. “It’s his wife, he can do what he wants with her” and “if the husband was present it wasn’t rape”. I was “naïve” claimed another man who raped an unconscious woman. Many of them have hired defence lawyers who attempted to blame Gisèle for the rapes they committed. They asked her about her sexual desires, “don’t you have tendencies that you are not comfortable with” and questioned whether she really was unconscious or just pretending. “There’s rape and there’s rape” one of them told her.

“No. There are no different types of rape”, Gisele replied, “Rape is rape”.

While there are 50 men on trial, another 30 men in the videos have not been identified.

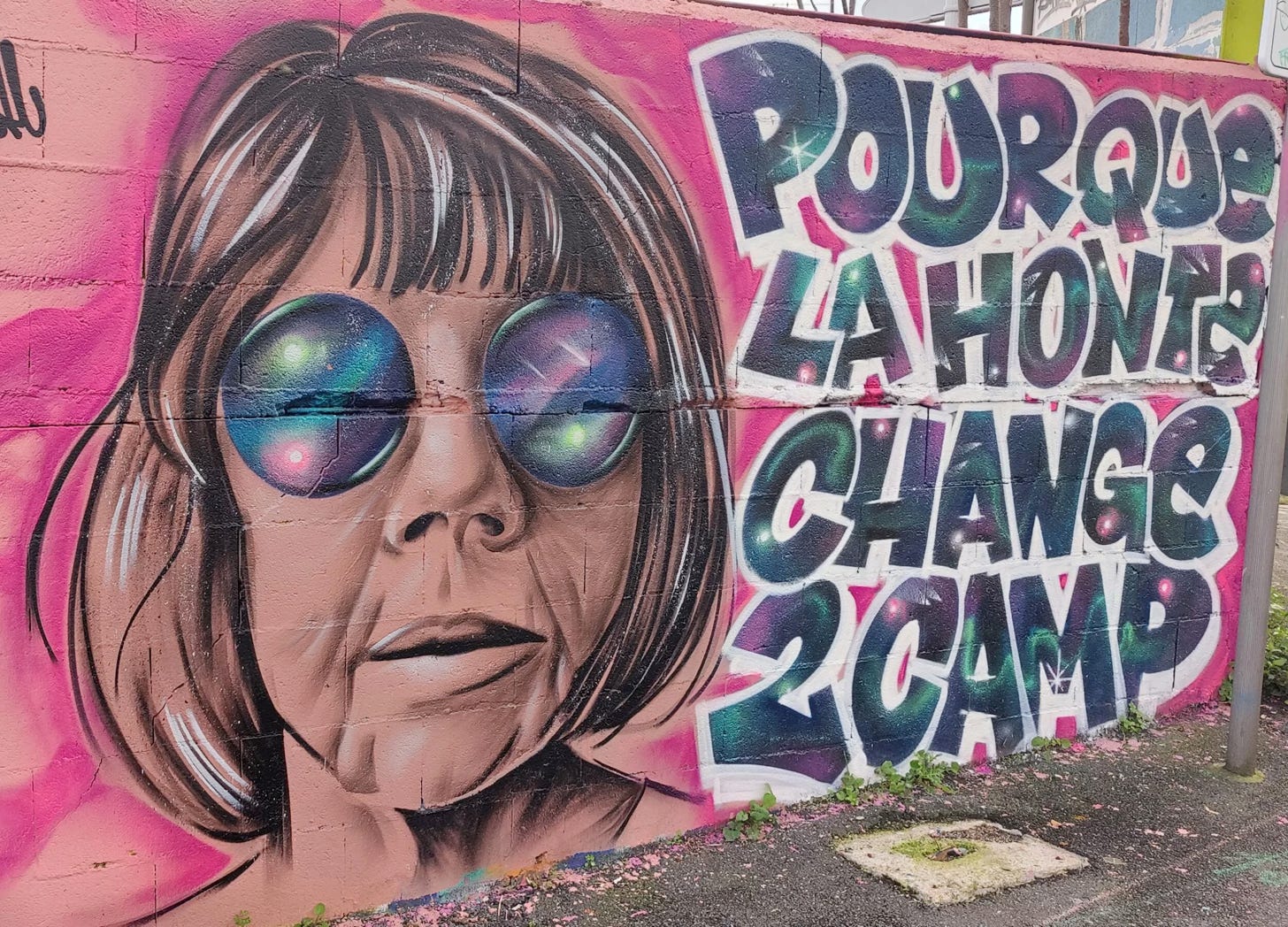

Gisèle Pelicot could have stayed anonymous. She did not have to become a global avatar for raped women. She chose to do it because she said, “I wanted all woman victims of rape – not just when they have been drugged, rape exists at all levels – I want those women to say: Madame Pelicot did it, we can do it too. When you’re raped there is shame, and it’s not for us to have shame, it’s for them”.

She is right of course. Shame does not belong to people who had no choice in what someone else did to them. And yet, this is far easier to say than to believe. Shame is common among people who have been subjected to sexual violence. It crosses all cultural, age, religious and gender lines, although all those factors can influence its impact.

What is shame?

In the 1970s, American psychiatrist Helen Block Lewis pioneered the ongoing research into the difference between shame and guilt, and how they impact our relationships with ourselves and the world.

Shame is far more damaging than guilt (what we feel about a wrongful act that can be redeemed and forgiven) or embarrassment (what we feel about other people’s perception of our actions). Shame is a deep belief that the entire self is inherently unworthy. It’s the cold, uncaring voice in our heads that says, “I am not good enough. I will never be good enough. I do not deserve love or consideration. My pitiful attempts to be loved or respected only prove that I am irredeemable, contemptible and vile”. Shame is about who we are, not what we do. Shame can be felt to different degrees, but at its worst it murders the soul and explodes into violence against the self and others. It can be corrosively destructive, far more so than any other emotion. Anger or rage can be clarifying, even redemptive when they reveal and give strength to redressing injustice. Shame, when it is hidden and unredeemed, can only diminish.

Some cultures use shame as a corrective tool to discourage behaviour that damages the community, but it’s tied to public forgiveness and redemption not rejection and unworthiness.

In her book, The Shame Machine, Cathy O’Neil writes about the shame clowns of the Hopi people, who live in northeastern Arizona. The clown’s bodies and hair are covered in clay and, as part of a community festival, they imitate and caricature shameful behaviour. The premise is that they are innocent children who do not know how to behave, but slowly learn to become more honourable, more Hopi. The clowns sometimes pick out individuals who have broken taboos or ethical rules and ridicule them in front of the community. The point is to reinforce behaviour that benefits the entire community and help transgressors learn better behaviour. But the ceremonies do not end with shaming. O’Neil writes that “both the clowns and their shame targets can receive formal forgiveness. With that, the shamed return to the tribe in good standing – though aware that others will be keeping an eye on them.” Shaming in this example is directed at the behaviour not the entire person. It is redemptive, not hidden or secretive, and designed to teach the entire community to concentrate on collective rather than individual benefit. This is very different to the shame experienced by people who have been raped or sexually abused.

Rape Shame

“I don’t know why people only talk about rape and young people. What do they think happens to those girls and young women? Do they think rape goes away? That we get over it and life goes back to what it was before? Maybe it does for some people, but I don’t think that happens for most of us. It changes you and you can’t change back. I’m almost 70 but I can still see the girl I was before it happened. She walked taller and held her head up higher. She trusted people and life to treat her well. She had faith in herself. She would not have grown up to be the woman I became. It’s not that it ruined my life, it just changed my life, and I didn’t have a choice about that.’

Penny*, raped when she was 16

“I know I’m not the one who’s supposed to be ashamed. Like, we’re all told that, right? And I don’t…I guess…. But I wish I’d done things differently. One of my friends asked me why I was with him when we all knew what he was like. And I kinda knew, like I knew he had done something to another girl, but I didn’t really know what. I didn’t know what rape was, or how easy it would be for him to do it. I didn’t think he would ever be mean to me. I guess that makes me kinda stupid, huh?”

Jessie*, raped when she was 16.

Penny and Jessie were both raped by boys only slightly older than they were at the time. They were both initially flattered by what they believed was romantic interest and then stunned when the boy they thought was cute and smart and funny turned into a rapist at the first opportunity.

Penny is almost fifty years older than Jessie. She adjusted herself and her life to fit into a world where 16 year old girls are raped by cute boys, and she says she learned to find joy again. “I don’t want it to sound like I’m some poor, broken thing. I’m not. I’ve done a lot, I’ve had a lot of fun along the way, and I’ll have more before I’m finished. It’s just that I know my life would have been different if it hadn’t happened. All those young years wasted on fear and hatred and not being able to do things. He put me on a different path. One that was much harder to walk, so it took me much longer to get where I wanted to go. I didn’t get nearly as far as I would have if I’d been allowed to be the person I was before it happened.”

Jessie is still trying to understand her path. “I don’t want to be just ‘the rape victim’. That’s never going to be who I am. But yeah, I think I am different now. I wish I could go back to being that stupid girl who thought boys were nice. But I don’t know. Maybe that’s why it happened?”

Neither of them reported the rape to police. Penny said she didn’t want her parents to know about it. “Not that they would have rejected me. They were lovely and would never have done that. But they would have been heartbroken. I couldn’t do that to them. I couldn’t bear their pain as well as my own, so I stayed quiet.”

Jessie says she didn’t report because “it wasn’t really rape. I mean it was because he forced me to even when I tried to make him stop. But I went to the house with him, and I was texting my friends about how cute he was. They told me not to go anywhere with him and I didn’t listen. I thought he was nice and they were wrong about him. No one would believe me after that. Even [her friend] said it was my fault for going with him.”

Even though Penny and Jessie both said they knew they shouldn’t feel shame, they both felt shamed by a boy’s choice to rape them.

Rape shame is counter intuitive – why should another person’s choice to commit such a terrible crime incite shame in the person who had no choice in what happened? The X factor that turns this conundrum into terrible emotional logic is the power of rape myths. I outlined them in much more detail in part two of this series, but essentially, rape myths are a set of beliefs about ‘real rape’ that make women responsible for being raped and men not answerable for committing it.

People who have internalised rape myths are more likely to feel shamed by rape, as are people (like Jessie) who get victim blaming responses when they tell people about the rape, but rape shame can exist even without this reinforcement. Women who have been raped sometimes believe the rapist chose them specifically because he saw them as someone who could, even should, be raped. Penny, for example, told me that for years she believed he saw something “weak or dirty or wrong, something in me that made it ok to do what he did”.

While a pre-existing feeling of shame exacerbate rape shame, it is not a failing in people who have been raped that they feel this way. It’s not a weakness or overreaction. It’s a result of the rape, like a bruise is a result of a whack. As one research paper described it, “degradation, humiliation, and worthlessness communicated by the rapist is likely to be internalized by the victim, particularly if this message is consistent with widely prevalent attitudes about women and sexuality.”

Rape shame contributes to underreporting and all those silent women who never tell anyone about what a man chose to do to them. It exacerbates PTSD and depression and could even contribute to suicide (please call one of the helplines at the end of this article if you feel that this could be happening to you – help is available and it works).

The overwhelming evidence that links rape myths to rape shame proves that one of the most powerful things we can all do to make shame change sides is to expose rape myths as destructive and dangerous lies. Every news headline, tv show, meme, “joke”, police report and piece of legislation that leans on rape myths contributes to the power they have over shame. Every person who says this is a lie, this is hurting people I care about, this is just plain wrong, is contributing to dismantling that power.

Gisèle Pelicot, in a truly stunning act of courage, stood up to the world’s acceptance of rape myths. The very least the rest of us can do is give a disgusted snort and a powerful “that’s just bullshit” when we see or hear rape myths in action.

* Penny and Jessie are pseudonyms and some details have been changed because both of them wanted to remain anonymous. Penny wanted to keep her experience private. “I don’t want people to read your thing and think they can talk to me about it. They can’t. But they won’t believe that if I let you put my name in there.” Jessie was afraid of her friend’s reactions. “They’ve all stopped talking about it now but if you use my real name they’ll start again, and I just can’t deal with it.”

This is part three in an ongoing series. Part four will look at why men who rape rarely feel guilt or shame for their crime but despite this, shame is often the driving force behind sexual violence.

Part Two: Understanding Rape myths

If you want to read the next instalments in the series and haven’t already subscribed, you can sign up below. I will do my best to keep them all outside the paywall, but if you can afford to subscribe it’s only $10 a month and every subscriber helps me slice away time from chasing paid work to do this work.

More Stuff

20% DISCOUNT plus free postage on any book purchase from my store.

Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children

Fixed It: Violence and the Representation of Women in the Media

Teaching Consent: Real Voices from the Consent Classroom

Discount code: 20Fairy

Podcast: The Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children podcast, loosely based on the themes in my book of the same name, is out now. You don’t need to read the book to listen to the podcast, but you can find out more about both here.

Helplines

In an emergency, where you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call police on 000

If you want to ask for anonymous advice for yourself or someone you know, call one of the helplines listed below or talk to a trusted GP or nurse practitioner at your local medical centre.

1800RESPECT

24/7 support for people impacted by sexual assault, domestic and family violence and abuse.

Ph: 1800 737 732

www.1800respect.org.au

Sexual Assault Crisis Line

24/7 Support for victims of sexual assault

Ph: 1800 806 292

www.sacl.com.au

Full Stop Australia

24/7 National violence and abuse trauma counselling and recovery service

Ph: 1800 385 578

www.fullstop.org.au

Men’s Referral Service

24/7 Support for men who use violence and abuse.

Ph: 1300 766 491

www.ntv.org.au/get-help/

Blue Knot Foundation

Phone counselling for adult survivors of childhood trauma, their friends, family and the health care professionals who support them. Available between 9am and 5pm, every day.

Ph: 1300 657 380

www.blueknot.org.au

Lifeline

24/7 crisis support and suicide prevention services.

Ph: 13 11 14

www.lifeline.org.au

Suicide Call Back Service

24/7 suicide prevention support

Ph: 1300 659 467

www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au

I love this series (and hate that there's a need for it). Your research and rhetoric are excellent. Looking forward to your new book!

https://federicosotodelalba.substack.com/p/drugs?r=4up0lp