Sector Speak Part 1: the language of violence

After years of watching media use language to minimise violence, render perpetrators invisible and dehumanise victims, it is horrifying to see exactly the same linguistic tricks consuming sector speak

“If I do not speak in a language that can be understood, there is little chance for a dialogue.” bell hooks, Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, 1989

Almost ten years ago I started the Fixed It project, challenging the way the media reports on men’s violence against women. While I still see the occasional egregious reversion to old habits, it’s genuinely reassuring how much media reporting has improved in the decade I’ve been monitoring its progress.

News articles in 2025 almost never talk about the once ubiquitous ‘jilted lover’ who ‘just snapped’ and killed his ‘cheating girlfriend’. Nor do they talk about ‘good blokes’ who ‘fell from grace’ when they raped ‘drunk teenagers’ or ‘loving fathers’ who were holding the smoking gun when their children ‘tragically died’. Even ‘star footballers’ no longer ‘face a career in ruins’ when they have to miss a few team practices because they’re on trial for sexual assault. Ten years of persistent advocacy from many different people and organisations has forced news media to get much better at using the active voice and removing tired old cliches from their reporting.

This improvement, however, only highlights the concurrent increase in passive voice, repetitive terms and dehumanising language that comes almost entirely from the people who work so hard to alleviate the cause and effects of men’s violence.

The organisations that research, respond to, advise on, and prevent gender based violence (often referred to as ‘the sector’) have developed a swathe of minimising and subverting linguistic tricks that are now standard in almost all discussion of violence.

The three main (but not the only) language culprits are:

Passive voice: the idiom of the invisible, unaccountable perpetrator.

Jargon: wordy, distancing terminology designed to exclude and intimidate people unfamiliar with sector vernacular.

Semantic saturation: the process of repeating a word so often that it loses meaning.

Each of these three are dangerous enough on their own, but used in combination with each other, their effects are exponentially increased.

Together, they become sector speak, and they are as dangerous as any dehumanising language can be.

Digging deeper into sector speak

It’s useful to know a bit more about how passive voice, jargon and repetition work to undermine ideas.

Passive voice: The idiom of the invisible, unaccountable perpetrator

In grammatical terms, voice describes the relationship between the verb in a sentence and the subject and object of that sentence.

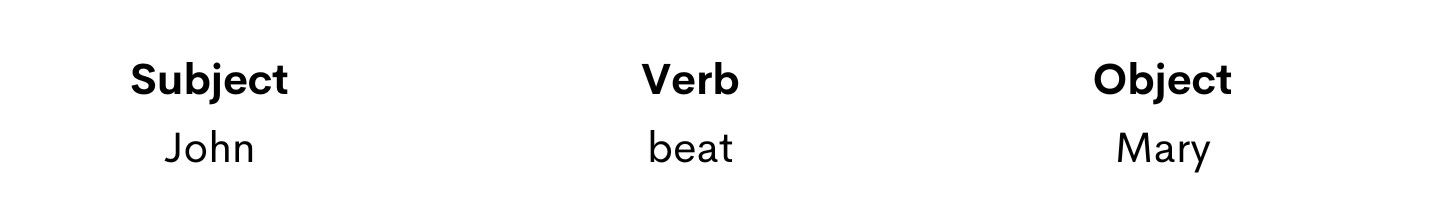

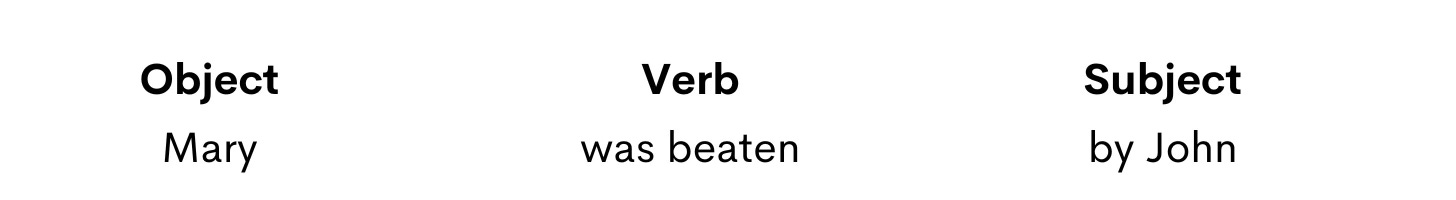

In the active voice, the subject performs the action of the verb on the object. In the passive voice, the object receives the action of the verb.

The easiest way to make sense of this is using examples. I’ll use the example Jackson Katz used in his TED talk (still far too relevant after almost 13 years).

John is the subject.

Beat is the verb.

Mary is the object. (I am very uncomfortable with using the word ‘object’ to describe any woman, let alone a woman being abused by a man – even if she is fictional – but this is not the time or place to start renaming grammatical terminology).

In the active voice, the subject is first, then the verb, then the object.

In the passive voice, the order is reversed, and the object is the recipient of the action by the subject:

In the active voice, the sentence isn’t complete without the subject and the object.

John beat… or …beat Mary are not complete sentences.

In the passive voice, the sentence is complete without the subject:

Mary was beaten.

The passive voice without the subject is a way of implying that either you don’t know who beat Mary or that knowing who beat Mary isn’t relevant to the information you’re conveying.

The APA style manual recommends using the passive voice when it is more important to focus on the recipient of the action than on who performed the action. Journalists and editors often used to use passive voice to erase violent men from headlines and news stories about the choices made by violent men.

Now, it’s the standard sentence construction in almost every sector publication, as demonstrated with some examples and simple fixes:

The National Plan to End Violence Against Women and Children

The National Plan to End Men’s Violence Against Women and Children

Too many women are lost to family violence

Violent men kill too many women

It’s important that victim-survivors are believed

Police must take victim-survivors seriously

We must believe victim-survivors

It’s important that I believe people who tell me they have been abused.

Ending violence against women is a priority

My priority is ending men’s violence against women

Jargon: obscure, dehumanising terminology

Sector speak is full of acronyms and jargon.

The PUV frequently deploys DARVO tactics against the VS in FDSV.

For anyone familiar with sector speak this is a simple sentence and a very basic concept. For anyone else it’s a meaningless collection of words and letters.

Even if all the acronyms were removed, the sentence is still just a collection of concepts, not a description of a person and their choices and actions:

The person using violence frequently deploys deny attack reverse victim and offender tactics against the victim-survivor in family domestic and sexual violence.

Rather than digging through the very long list of sector jargon, it might be more helpful to take a close look at two of our most ubiquitous terms: ‘victim-survivor’ and ‘lived experience’.

Victim-survivor

In a sector full of repetitive jargon, victim-survivor has been so over-used that it is now used - unquestioningly - as a synonym for person in every statement about people who have lived through violence. Or even people who didn’t survive - I was at a domestic violence conference a few years back where a very dedicated and credible researcher gave an entire presentation on ‘victim-survivors of domestic and family violence homicide’. That sentence was in her slides. More than once. And no, she was not talking about family members of murdered women. She was talking about women who had been killed. None of whom were survivors.

The victim/survivor dichotomy entered public debate in the 1960s and 70s when people who had lived through the holocaust were often separated into victims (seen as passively existing and alive only by chance) and survivors (bravely working to save themselves and others). Victimhood was perceived as being about shame and cowardice while survivors were, by implication, heroes who were stronger and more deserving than the people who were killed. ‘Victim-survivor’ was coined to erase that divide and remove shame from all the people targeted by the Nazis during the holocaust.

Feminists in the 70s through to the 90s started using the term for very similar reasons. Tying the terms together was supposed to erase the negative connotations of both, but it seems to have entrenched the effect of labels, both good and bad.

“I stopped when I saw the words Rape Victim in bold at the top of one sheet… I paused. No, I do not consent to being a rape victim. If I signed on the line, would I become one? If I refused to sign, could I remain my regular self?” Chanel Miller, Know My Name: A Memoir, 2019

A victim is defined by the harm someone chose to do to them and a survivor by their power to heal and live afterwards. A victim-survivor is both these labels, but they still exist only in relation to the thing someone chose to do to them.

The word ‘victim’ comes from the Latin, victima, meaning an animal sacrificed to the gods. While the word is embedded in criminal courts and police reporting, it’s almost never used on its own in the sector. ‘Victim’ carries connotations of someone who is weak, helpless and pitiful, even shameful in their inability to defend themselves. After being deprived of the power to decide what someone else can do to their mind and body, it’s entirely understandable that someone who has lived through abuse would fiercely reject language that defines them as a powerless person.

The term ‘survivor’, however, is not universally embraced. Some people passionately object to being labelled ‘survivors’ because they see the term as a demand for evidence of recovery, which may not be true or even possible for everyone. Others refuse it because they think it minimises violence that is not life threatening but is still painfully traumatic - if the violent person was never going to kill you can you call yourself a survivor? And if not, does the ‘victim-survivor’ dichotomy mean ‘victim’ is the only other option?

Research with university students who had been raped shows some people might be reluctant to take on the ‘survivor’ label because it indicates they don’t need support or justice or because it implied a level of personal power that meant they should have been able to defend themselves against the rapist.

Other research suggests the label risks perpetuating the romanticising of violence, where abuse is perceived as a life lesson or a moment of personal growth that turns a ditzy teenager into a wise and empathic woman. Almost as if someone should be grateful to their abuser for helping them become a better person.

Trauma does not make someone a better person. In fact, trauma can make a good person behave like an asshole. A reactive, raging, self-centred, unpredictable, hurtful, self-medicating asshole. This behaviour can be an entirely reasonable, even healthy response to deep injury and it’s very common in people who have been abused. But it’s not the romantic, self-sacrificing, if-I-can-stop-this-happening-to-one-other-person-it-will-all-be-worth-it ideal survivor response. Erasing that raging, messy person from the victim-survivor archetype builds a mythology that ‘good’ victim-survivors find healing in noble and selfless service to others. That may be true of a few people, but for most people, recovery takes years and requires considerable time, effort and focus on the self. No one should ever feel shamed for making that effort on their own behalf.

The victim-survivor myth might be more about offering comfort to observers who don’t want to think of violence as a terrible story with no happy ending. Or even no ending at all.

There is rarely a binary choice between triumphantly healed and permanently damaged. Both can exist in the same person. Victim-survivor as a term might offer some path between the duality but it still defines and limits an entire person to a single experience.

A person is still a person after (and during) violence. They have complexities and flaws and interests and aspirations that exist outside their trauma and even if trauma makes their ambitions more difficult to achieve, it does not have to create or define them. No matter how much lived experience they have.

Lived experience

What other kind of experience is there? Using tautologies to produce jargon is a hollow sales trick that should have no place in any discussion of people who have been abused.

Having said that, there is history to this term. Until very recently, policy, response and services for many groups of marginalised people were often designed and implemented without any input from the people who actually used the service. It was paternalistic, frequently racist, and usually unhelpful. As the sector grappled with this, they searched for language that would give greater respect and prominence to people who had first-hand experience of living through violence. ‘Lived experience’ was the term they chose to differentiate people who had that first-hand knowledge from people who had (or believed they had) expertise in structural responses to violence.

That first-hand knowledge is a vital component of any service. I don’t want drive a car designed by someone who has never had a driver’s licence, no matter how much engineering expertise they have. But I also don’t want my car designed by someone whose only qualification is that they survived a terrible car accident. The best driving experience will come when not just those two people, but an entire team of people (like them and unlike them) work together. A group of experienced engineers who can genuinely listen to and care about thousands of people who have been in car accidents in many different conditions and circumstances. They also need to hear from people who have avoided accidents or had the split second timing and tools to turn a devastating crash into a minor bingle.

I’m sure you can see where I’m going with the very tortured analogy.

Surviving something does not make someone an expert on the thing that almost killed them. It does make them an expert in their experience of it – how they felt, what they thought, whether the responses they got from crisis services were helpful or hurtful, what else they needed, how the experience affects their life – no one else could possibly know these things or should ever claim to know them. And that knowledge is invaluable to the people who design and implement response and recovery services.

The issue with lived experience is not in its meaning or intent. Where it becomes a problem is when the meaning of the term moves from respect and prominence to veneration and mythology.

Asking people to give input to service and policy is very different to demanding public advocacy. Traumatised people who have barely had time to understand what was done to them cannot become experts in every form of violence. Asking them to do so is grossly unfair and to then insist that they unzip themselves on demand and spill out their pain for the eager consumption of journalists and social media followers is replicating abuse, particularly when we know how they will be dehumanised, idolised and vilified across the political spectrum. Every action, every expression, every smile (or failure to smile) measured against the ideal survivor standard and used as justification to strip a person of their personhood. It’s grossly unfair and it sets up deeply unrealistic expectations for people who think they can find healing by becoming the next Rose Batty if they share their story. For almost all those people, their story will vanish within 24 hours and no one will remember the courage they had to find and hold when they revealed their scars to the world.

Input does not require veneration. There is no moral authority or worthiness in surviving violence or in being able to speak publicly about abuse’s graphic details. Sometimes survival is simply a matter of luck. Sometimes the opportunity to speak happens in a single tortured moment, as it did with Rosie Batty. Sometimes it’s denied to people who do not fit the perfect victim myth or who aren’t young, white, or photogenic enough for mainstream advocacy. Some people cannot overcome the silence and shame imposed on them by violent men and equally violent patriarchy. Others want to speak but cannot because the man who hurt them is still too much of a threat. Far too many others believe the abuse they experienced wasn’t severe enough to give them real lived experience.

‘A journalist friend of a friend contacted me looking for a survivor quote for a story. I told her what happened to me and her response was, “so he didn’t actually rape you then?” He threatened me and terrified me and hurt me, but I managed to get away before he actually got into my vagina, so I guess that means I wasn’t survivor enough.’ A 28 year old woman who lived through an attempted rape

The lived experience veneration also forces people to choose between becoming a lived experience advocate or a sector expert because the term exists only to differentiate between the two. The truth is that many people in the sector have first-hand knowledge and expertise. Men’s violence is far more prevalent than commonly cited statistics indicate and it’s ludicrous to assume that the people who can publicly declare their lived experience are the only victim survivors.

Semantic satiation: repetition eliminates meaning

Semantic satiation (also known as semantic saturation) is what happens when a word is repeated so often that it stops being a word and becomes nothing but meaningless sounds. This effect was documented as early as 1907 and ongoing research shows that too much repetition not only eliminates meaning of the repeated word, but it can also diminish people’s ability remember and connect meaning to related words and concepts.

Apply that theory to the term ‘victim-survivor’ or ‘family and domestic violence’ or ‘coercive control’. When these terms are the only words anyone uses to describe these concepts, the repetition is massive and endless. Anyone hearing it can’t help but lose understanding of and empathy with ‘victim survivors of family and domestic violence and coercive control’.

So, people who have already been dehumanised and terrorised by someone who claimed to love them are then collectively dehumanised and diminished by people who claim to support them.

This is the reality of sector speak.

Once again, I underestimated how much needed to go into this piece and it was getting ridiculously long. Later this week I’ll post part two of this piece, covering the causes and effects of sector speak.

The Sector Speak posts have a wider application than just rape and sexual assault, which is why I’ve not listed them in the Rape is a Theoretical Crime series. They are, however, highly relevant to the series and the reason I wanted to post them this week is so I can refer to them in later instalments of the rape series.

In 2025 I’m starting PhD at Monash University to research men who have committed sexual violence, what they think about masculinity and shame, and whether there is anything we can learn from them to improve prevention education.

Paid subscriptions support my research and in return will receive plain language summaries of my research along the way.

Discount offer for readers

20% DISCOUNT plus free postage on any book purchase from my store.

Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children

Fixed It: Violence and the Representation of Women in the Media

Teaching Consent: Real Voices from the Consent Classroom

Discount code: 20Fairy

Podcast

The Fairy Tale Princesses Will Kill Your Children podcast, loosely based on the themes in my book of the same name, is out now. You don’t need to read the book to listen to the podcast, but you can find out more about both here.

Helplines

In an emergency, where you or someone you know is in immediate danger, call police on 000

If you want to ask for anonymous advice for yourself or someone you know, call one of the helplines listed below or talk to a trusted GP or nurse practitioner at your local medical centre.

1800RESPECT

24/7 support for people impacted by sexual assault, domestic and family violence and abuse.

Ph: 1800 737 732

www.1800respect.org.au

Sexual Assault Crisis Line

24/7 Support for victims of sexual assault

Ph: 1800 806 292

www.sacl.com.au

Full Stop Australia

24/7 National violence and abuse trauma counselling and recovery service

Ph: 1800 385 578

www.fullstop.org.au

Men’s Referral Service

24/7 Support for men who use violence and abuse.

Ph: 1300 766 491

www.ntv.org.au/get-help/

Blue Knot Foundation

Phone counselling for adult survivors of childhood trauma, their friends, family and the health care professionals who support them. Available between 9am and 5pm, every day.

Ph: 1300 657 380

www.blueknot.org.au

Lifeline

24/7 crisis support and suicide prevention services.

Ph: 13 11 14

www.lifeline.org.au

Suicide Call Back Service

24/7 suicide prevention support

Ph: 1300 659 467

www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au

Great article, loved it Jane. Your discussion also took my mind to the activist or resistance traditions that birthed these terms, prior to their uptake in psychology and social work and DFV (sorry, couldn't resist) discourse. As a researcher who has done substantial work in the field, the use of survivor for the person who has experienced violence in your presence (e.g. when seeking services or counselling, or taking part in research) is used as a form of validation. Not just that they survived violence, but validation and recognition of their agency of having kept themselves/ their children alive, which sometimes meant being the victim. Also, there is lots of this thinking from resistance movements and participatory research, which implies that a person with lived experience who resists has been conscientized, come to unravel the structural forces of their own oppressions, thereby giving them specific insights into its resistance.I think partly the issus is that these terms get coopted from what is essentially the Black/third world anti-colonial freedom movements, and become depoliticized and neutered as they enter the academy.

Thank you, Jane! Powerful and clearly explained. It's so tempting to use jargon when I assume that my readership is familiar with the concepts. I need to remember that not everyone who reads a particular piece has the same level of immersion I might.

I especially value your critique of that dreadful phrase, "lived experience"! I scream silently whenever I encounter it - yet I've succumbed on occasion when it's seemed too difficult to state the obvious: first-hand experience.

When I noticed my psychology using the term I asked her what she meant. She made a distinction between "experiencing" first-hand ("lived experience") as opposed simply to "knowing about" something second-hand, through reading, watching videos, listening to podcasts, or even vicariously. (This is my understanding of what she conveyed, not her exact words.)

I'm still wrestling with it on the grounds that the word "experience" on its own surely indicates "first-hand" or (shudder) "lived." With the arguable exception of vicarious experience, I'd feel something of a false actor if my primary or only "experience" of an event or series of events came from reading, watching, listening, etc, rather than actual participation in those events.

For instance, I know about the Black Friday Bushfires and the devastation they caused - but I would *never* claim to have any "experience" of those events. I would take it as given that anyone who stated they had experienced the bushfires was present, at some time, while they occurred.

Time to end! With thanks again! And apologies for such a lengthy response.