Invisible children killed by visible parents

When parents kill their children, there is almost always a history of domestic violence and child abuse. Why is it so rare that we hear from, or even about, the children who live with violent parents?

There are few things more horrific than killing a child. Children are so small, so defenceless. And have so much life unlived. It’s unfathomable that someone could simply choose to end all that time, passion, and potential before it even had a chance to grow.

Thankfully, child murders in Australia are rare.

Of the 1,957 people killed in Australia between July 2010 and June 2018, 202 were children.

Source: Australian Institute of Criminology, Homicide Victims data

One of the most incomprehensible facts about child killings is that the person most likely to kill a child is their parent, step-parent, or person who has parental responsibility to the child. In other words, the person we believe will (or should) love and protect them from all harm.

Most parents love their children deeply and do the best they can to keep them safe and happy. It’s more difficult than it should be and none of us can ever claim to be a perfect parent. For some people, all their best intentions and staunchest defences are not enough to keep their children safe. Some, incomprehensibly, choose to harm their children. A very few choose to kill them.

No matter how rare it is that people choose to murder children, no healthy society can ignore any level of child killing. It is imperative, if we are to end (or at least reduce) the number of children killed, that we understand the circumstances in which such horrific crimes occur. Which is why Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) and the Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network undertook an intensive study of filicides in Australia. The information based on primary source material including coronial files, police briefs of evidence, sentencing remarks, and service contact data.

Filicide: The homicide of a child or children under 18 years of age by their parent/s and/or parent equivalent/s.

Between July 2010 and June 2018 in Australia there were 113 cases of filicide, in which 138 children were killed.

106 children (76%) of filicides occurred in a context of domestic and family violence (DFV)*. Which means were killed after they had survived any combination of:

Child abuse: any physical, emotional or sexual violence towards the filicide victim or their siblings.

Intimate partner violence: any intimate partner violence involving the child’s parents.

* DFV includes a spectrum of physical and non-physical abuse within an intimate or family relationship. DFV behaviours include physical assault, sexual assault, threats, intimidation, psychological and emotional abuse, social isolation and economic deprivation.

Source: Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: Filicides in a domestic and family violence context 2010–2018

We hear a lot about the violence inflicted on women by men who claim to love them. We’ve rallied and protested and marched and written millions of words, soaked in rage and grief for the women abused by men. But we rarely hear about and never hear from the children who are growing up with violent and abusive parents.

At least 44 % of women who live with violent men (and were able to disclose this to a stranger taking a survey) had children in their care at the time. This figure is likely to be underestimated as the survey group excluded anyone living in a caravan park, motel, refuge, friend or family member’s home, sleeping rough.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016), Personal Safety, Australia, ABS Website, accessed 4 July 2024.

Apart from the people who work with survivors and perpetrators of violence, most of us know about domestic violence and child abuse because we’ve either lived through it ourselves or people we care about have told us their stories. The rest of our information mostly comes from the media.

Some reporting on gendered violence is outstanding. It’s nuanced, contextual, well informed and useful. Jess Hill’s 2015 reporting on the nature of domestic violence and the dangers of family court, followed by her award-winning book, See What You Made Me Do helped change the public understanding of domestic violence in Australia. Nina Funnel’s award winning journalism on the legal system’s deliberate silencing of child abuse victims led to national change in how we understand sexual abuse survivors. Hayley Gleeson’s work at the ABC and Sarah Ferguson’s Hitting Home series stand out, I’m sure there are others, but these are the well-resourced and rare feature pieces, not the routine reporting on daily violence churned out by general news reporters. As I’ve written before, while there are over 200 sports journalists and at least another 200 political journalists in Australia, there are no journalists with a specific remit to reporting on gendered violence in any newsrooms.

Nowhere is this deficiency more obvious than in the reporting (or absence of it) on the hundreds of thousands of children who live with abusive men (no, not all men are violent, but most violence is committed by men, this fact is important for effective prevention and response work).

There is a formula to daily news pieces on gendered violence. Tim Dunlop and I put this prompt into ChatGPT a while back: “Give me, in the style of the ABC, an article about domestic violence with a survivor story at the top, a truncated quote from a CEO of a structurally underfunded Not-For-Profit in the middle, some prevalence stats with no context at the end, and finish off with some generic helpline numbers.” The result was indistinguishable from most articles published by almost any news outlet in Australia.

You can’t use that formula when you’re telling children’s stories. All Australian states have laws preventingjournalists from identifying child victims of violence. With good reason. Many adults struggle to understand the consequences of publicly sharing their stories of abuse and trauma1, so we cannot expect children to foresee all the consequences in all their possible futures and be able to give informed consent to interviews, photos, videos, quotes, and all the other standard tools of journalism.

When abusive men reach the apotheosis of violence and kill their partners or children, reporting on the killing of adults is still much easier. Adults have social media accounts full of photos and friends who can give heart-rending quotes, so content is easy to find. Murdered children become the also-rans who stumble along in their wake.

We can make children anonymous, up to a point. But there is a fine line between including enough truth to tell the real story and keeping back anything that could make the child identifiable. A step too far in either direction can have perilous consequences. Either a child identified and put in danger, or a story becomes so stripped of details that it is meaningless.

Even if journalists could find children who are not involved in criminal cases or still living in danger (which would trigger mandatory reporting and put the children into privacy protections) asking children to describe their memories and feelings about abuse requires expertise and ongoing support for months, even years afterwayrds. Journalists, at their best, are storytellers and verifiers of truth. They are not therapists or lawyers. Any ethical reporting, therefore, must ensure someone else can provide this care to children after the journalists are done. All of which takes far more time, money, care, and skill than is available to any newsroom.

How, then, do we talk about the children and teenagers who live with violence every day? At home. At school. At work. Online. They are not shielded just because we so desperately want them to be.

There are some adult survivors of childhood violence, such as Conor Pall who provide a much needed perspective, but it’s not something many people can do. And even if they could, adult memories of the past are not the same as children’s perspectives of their present. It’s better than nothing but it’s not the same as sharing the stories of children in crisis now, so we can know and act now.

At least 122 children between 2010 and 2018 survived the killing of a sibling. This is a conservative estimate of what is likely to be a much larger number of children who still live with the trauma of a sibling being killed by their parent.

Source: Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: Filicides in a domestic and family violence context 2010–2018

All of this makes it difficult (not impossible, but very, very difficult) to accurately, ethically and truthfully report the experiences of abused children. Lacking the time, expertise, and resources, most journalists simply avoid it and concentrate on reporting women’s experiences.

46% of children killed by a parent in a DFV context were under 3 years old.

More than 60% of children killed by a parent had recorded contact with police and/or child protection services and more than half of those had been in contact with services less than 3 months before the filicide.

Source: Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: Filicides in a domestic and family violence context 2010–2018

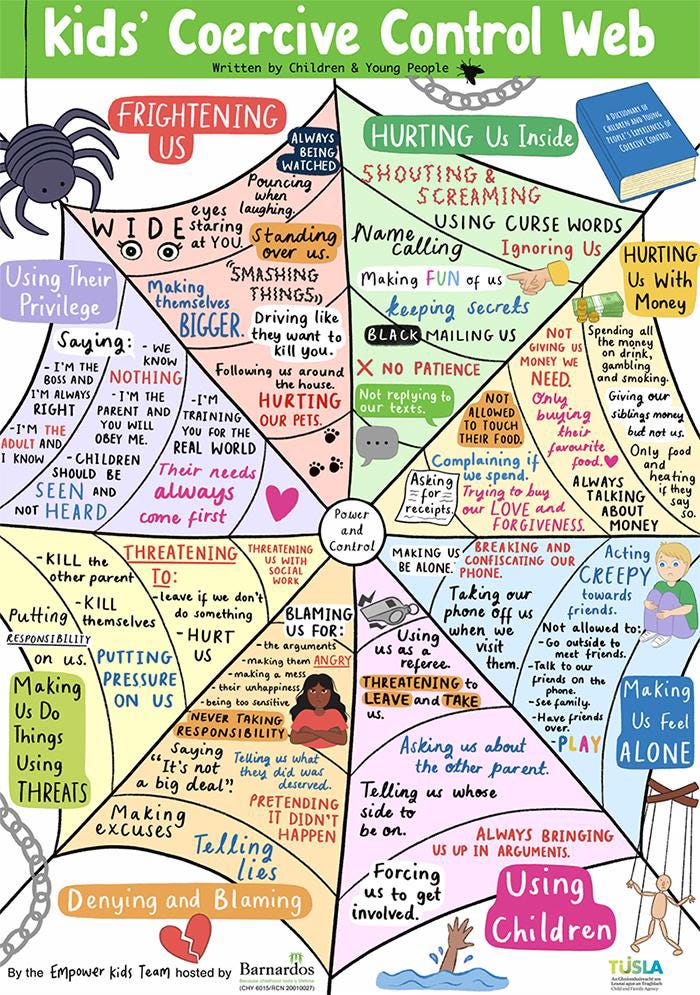

There are a few ways we can ethically and responsibly tell children’s stories in their own words. Some researchers and frontline services work with children for this exact purpose. Barnados in Ireland worked with young children who had experienced coercive control to produce this powerful image, along with other resources showing children’s stories in their own words:

Art is a powerful form of communication. These images on the Australian Childhood Foundation website are another example of how children can share their stories.

We can work with the people who work with children to develop visceral but de-identified stories to make their lives visible without endangering them.

I’ve sat in childcare centres and schools listening to experts responding to little children describe in excruciating baby lisps, how sometime is touching them or making them watch pornography. I’ve heard children throw out casual mentions of dad’s violent outbursts and watched teenage boys try to prove their worth and erase their shame by intimidating girls and female teachers. I’ve run workshops with boys barely out of adolescence who are there because they’ve stopped just a shade sort of criminal harassment and don’t even understand how they came to it. I’ve seen young boys stranded in the shadowlands between victim and perpetrator because they are both and neither at the same time. I’ve listened to girls talk about the importance of making sure they are nice and pleasing and empathetic, barely able to recognise that their own needs have value. I’ve listened to the boys who swear, in chocked up voices, that they will never be like their violent fathers. I’ve listened to the men who tell police and therapists and behavioural change groups about the fathers, unable to comprehend that they have already become their own worst nightmare. “You think I’m violent? You don’t even know violence. My old man, he was something else. I’m nothing like him.”

Those stories are difficult to hear, even more difficult to tell, all but impossible to live through. But this is what journalists, the tellers of truth and verifiers of fact, are supposed to do.

Many years ago, Margaret Simons told me that the purpose of journalism is to describe society to itself. It’s the second sentence in the Journalist Code of Ethics. More than two million children in Australia are being abused by people who are supposed to love and protect them, right now, today. Telling us about them and describing their lives to the society in which they live is the job of journalists and the responsibility of all of us.

There were almost 5.7 million children in Australia in December, 2023

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (December 2023), National, state and territory population, ABS Website, accessed 6 July 2024.

40% have been exposed to domestic violence

29% have been sexually abused

32% have been physically abused

31% have been emotionally abused

9% have experienced neglect

Source: Haslam D, Mathews B, Pacella R, Scott JG, Finkelhor D, Higgins DJ, Meinck F, Erskine HE, Thomas HJ, Lawrence D, Malacova E. (2023). The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from the Australian Child Maltreatment Study: Brief Report. Australian Child Maltreatment Study, Queensland University of Technology.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander data

I don’t know how many articles I’ve written about violence and poverty and injustice. Over the last 15 years it’s maybe coming up on a thousand? How ever many it is, that’s the number of times I’ve written variations of this sentence: “Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people are over-represented in this data.” Sometimes when I say this in public, I can see relief on white faces. It’s not going to happen to me it’s not going to happen to my children, all these numbers are Aboriginal children and that means it happens to people who aren’t like me. It’s the very essence of racism. This group I can identify by colour, faith, region, dress, something, they’re not the same as me. They don’t have the feelings like mine they’re emotionless, blank, muted, different and they don’t feel as I would feel when awful things are done to them.

Except, that they do. There is no group of humans who were born with a lesser or greater capacity for grief and joy.

Imagine your child being abused. Imagine your child being killed. Imagine your child being taken from you. Imagine you are powerless to get them back. Imagine you are blamed for their removal. Imagine how you would feel. Imagine a life of that feeling. Imagine the life of your surviving children. Imagine their children. Imagine them incarcerated, addicted, staggering under the weight of all the lives they carry. Imagine this happened to all your neighbours and cousins and friends. Imagine the world destroyed and created for them to inhabit. Imagine all the unimaginable things.

This exercise of imagination for white Australia is the reality of Aboriginal Australia. Statistics do not happen in a vacuum.

26% of filicide victims were identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander

21% of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander filicide victims were killed by a non-indigenous parent

16% of filicide offenders were identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander

Source: Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: Filicides in a domestic and family violence context 2010–2018

The full report on DFV-context filicides is on the ANROWS website. It’s long and technical. And painful to read. It’s not something everyone can get through. But everyone should, at the very least, know about it.

Key statistics on DFV-context filicides:

86% did not have any recorded family law proceedings.

83% of offenders were living with the children they killed.

31% of cases included separation as a characteristic.

93% of victims were born in Australia.

78% of offenders did not attempt or complete suicide afterwards.

8% involved the offender killing their entire family (child/ren and intimate partner).

85% occurred in a home belonging to the victim, offender or both.

47% were committed by assault with no weapon.

58% occurred in major cities (compared to 72% of the population living in major cities)

37% of offenders were in paid employment (compared to 66% of the population)

55% of victims were boys. (Australian research has consistently found that male and female children are victims of filicide at a similar rate, suggesting that gender does not play a role in filicide victimisation.)

26% showed evidence of pre-planning (premeditation may have existed in other cases but evidence was not identified in case files).

People who commit DFV-context filicides:

40% were the child’s biological father

27% were the child’s non-biological fathers

30% were the child’s biological mothers

2% are the child’s non- biological mothers

Source: Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network data report: Filicides in a domestic and family violence context 2010–2018

Grace Tame and Rosie Batty have both spoken about the cost of being the public personification of trauma. It’s high and it’s not something someone chooses or predicts. Even for women who do not become household names, the response can hurt. Many years ago, I talked to a woman who did an interview with a journalist from a major newspaper about being raped and what she described as “the almost equivalent violation” of her rapist’s trial. This woman was an adult and was working with a very ethical journalist. She was sure she knew exactly what was coming when her story went live - raging backlash on social media is the expected outcome for any woman who speaks publicly about men’s violence. She was ready for that. Grief, anger, and disbelief from her rapist’s friends and family. She was ready for that too and coped with it all remarkably well. Then, one day in a supermarket, a neighbour popped up in front of wanting to have a sympathetic conversation about sexual violence and all her protective barriers shattered. “When I knew it was coming, I had all my shields up. But I wasn’t prepared that day in Coles. I had a massive panic attack and they ended up calling an ambulance. If you’d told me even a week before that was going to happen, I’d never have believed you.”

This is the nature of trauma. Its effects are often unpredictable.